Olivetti’s Ivrea, Wallpaper magazine

Text Richard Cook

The concrete forecourt, its crisp air tangy with the scent of hurried cigarettes, the careless accretion of safety signage: it all looks so familiar, banal even. Men are smoking alone in crumpled shirtsleeves, with photo IDs around their necks. The sun is smiling weakly, as if through gauze. There is a light dusting of snow on the handsome Canavesana peaks to the north.

It’s almost noon and every 60 seconds or so the nearest lift disgorges another load. Another two or three workers step purposefully through the security gates out into the sunshine and head round the corner to the canteen. I head in the opposite direction.

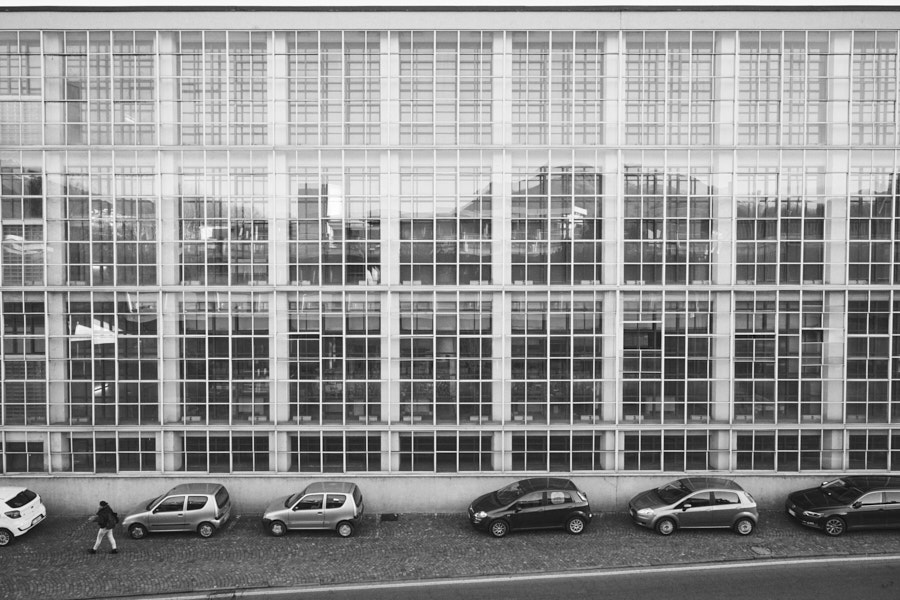

The entrance hall of the Olivetti Office Building is dominated by a remarkable Escher-esque hexagonal staircase, completed in 1964 to a design by the typewriter manufacturer’s futurist in-house designer Marcello Nizzoli. It features a bas-relief by the sculptor Andrea Cascella. All on its own, it announces we are in the presence of something truly remarkable, a space where art and commerce seamlessly come together.

In July last year, Unesco agreed. It placed the entire industrial area of Ivrea in northern Italy – including this office block and Gino Valle’s big brash 1980s neighbour, as well as houses, apartment blocks, factories, canteens and even a nursery school designed by the Milanese rationalists Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini – on the World Heritage List.

The Unesco citation said this company town of 25,000 people, just an hour from Turin, was ‘an ensemble of outstanding architectural quality that represents the work of Italian modernist designers and architects... one of the first and highest expressions of a modern vision in relation to production, architectural design and social aspects at a global scale.’

This first Olivetti office – a joint architectural effort by Annibale Fiocchi, Gian Antonio Bernasconi and the aforementioned Nizzoli – is one of 18 company sites, largely concentrated along Via Jervis, and two other principal locations to the east and west of town, that together make up this remarkable architectural patrimony. It is the vision, primarily, of one man.

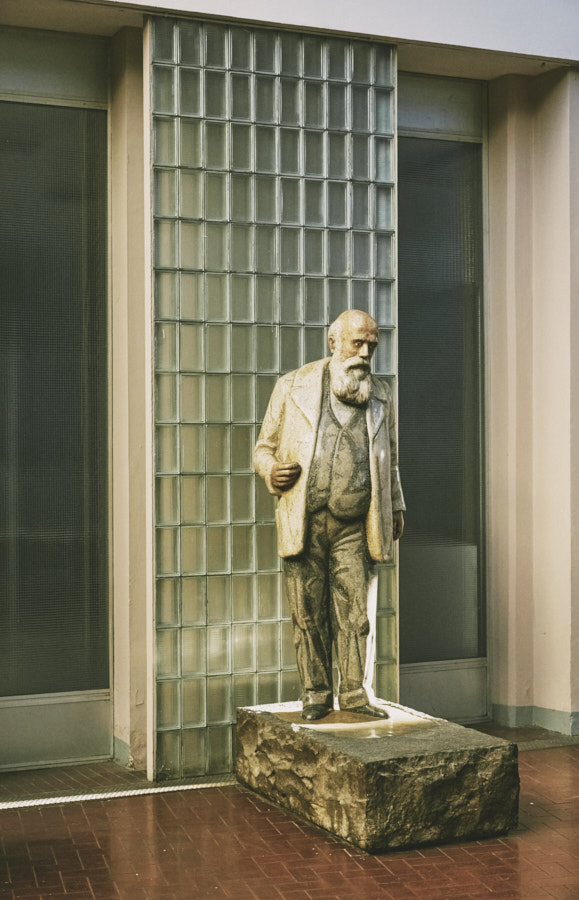

Camillo Olivetti founded the typewriter production business in 1908, but his son Adriano is the reason the company name still has relevance today. When he took over as general manager in 1933, Olivetti was still a small family concern. When Adriano died in 1960, its products were sold in more than 100 countries and the company was still growing. Ettore Sottsass had yet to design the iconic ‘Valentine’ portable model for which Olivetti is perhaps now best known.

Adriano was an early adherent of US engineer Frederick Taylor’s time and motion systems for industrial production. It was the key to his financial success. He was also that entrepreneurial rarity, a lifelong utopian idealist committed to the idea of enlightened community life and a passionate believer in the power of art and architecture to change people’s lives. This formed the basis of his artistic life. And Ivrea was his canvas.

His father had actually dabbled in this kind of corporatism himself. He had built houses for workers as early as 1926, erecting six simple single-family buildings in an area close to his workshops, but this was chiefly for the sake of convenience. In the 1930s, Adriano took this to a whole other level. He commissioned architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini to come up with a more ambitious, rationalist scheme that ultimately produced flats for 24 families, as well as rows of distinguished terraced housing and the services that these new residents needed. At a stroke, he dispensed with mere utility in the pursuit of something beautiful, something that he wanted not just to accommodate but to enrich his workers’ lives. At the same time, he was also cutting hours in the factories and increasing pay and, despite criticism from his business peers, watching productivity soar.

The architects were charged with building using strict ‘heliothermic’ standards, restricting building densities in favour of living areas that maximised light and space. The apartment blocks were capped at four storeys and the ground floors given over to services. Balconies and stairwells were finished with imported hardwoods, and blocks were separated by huge swathes of landscaping. A primary school was positioned through the trees nearby, and a library, medical centre and crèche soon followed, housed in the austere hexagonal slabs of the Social Services Centre on Via Jervis, completed by the same architects in 1959. In the rows of terraced housing intended for larger families, stairs and services were housed in a functional northern façade and the three southern storeys were opened out with glazing and balconies overlooking small vegetable gardens. Executive housing, designed by Marcello Nizzoli and Gian Mario Oliveri in the early 1950s, shared many of the same traits. Plaster rendering was interspersed with stone work, but the finish and materials were otherwise from a similar palette to that of the housing for ‘regular’ workers.

As the years passed, these residential schemes became ever more ambitious, especially after Adriano’s death. First there was the late-1960s peculiarity that was Roberto Gabetti and Aimaro Oreglia d’Isola’s subterranean Talponia or ‘Molehill’ complex, dug out of a hillside so vast that a huge underground service road runs behind the 81 apartments, marked by otherworldly Plexiglas circles at ground level.

The later housing schemes culminated in the Eastern Residential Units (formerly known as Hotel La Serra), designed by Venetian architects Iginio Cappai and Pietro Mainardis as part of a complex immediately, if not imaginatively, dubbed ‘the typewriter’. The vast space managed to combine ancient Roman ruins, a cinema, restaurant, conference hall, pool, several bars and stores, and 55 small apartments into its six concrete and steel floors – and still look like a giant typewriter. And not just any typewriter, but Olivetti’s ‘Lettera 22’ model, designed by Marcello Nizzoli, of course.

Something of the ideological discipline of Adriano’s vision was misplaced in much of the later work, but it’s equally clear that it had been his example that emboldened his successors to explore the world of art and architecture, even as the company was falling victim to a more brutal corporate age.

The challenge now, as Unesco has identified, is to preserve Adriano’s legacy. The Social Services Centre lies empty, a few more windows broken this year than a year ago, while the school moved out of the nursery building late last year. There is spare capacity in the office buildings and there is the air of an out-of-season resort about the town. But there is hope, too, and sensitive restoration underway at a couple of the still imposing terraced houses. It’s a long road, but it’s hard to think of anything more necessary. Adriano Olivetti wanted to change the whole world, one well-designed office, apartment, crèche, shop and cinema at a time. And who’s to say he didn’t manage it?